By Claire Bishop.

What does the term “installation art” mean? Does it apply to big dark rooms that you stumble into to watch videos? Or empty rooms in which the lights go on and off? Or chaotic spaces brimming with photocopied newspapers, books, pictures and slogans? The Serpentine Gallery announced its summer exhibition of work by

Gabriel Orozco with the claim that he is “the leading conceptual and installation artist of his generation” – yet the show comprised paintings, sculptures and photography. Almost any arrangement of objects in a given space can now be referred to as installation art, from a conventional display of paintings to a few well-placed sculptures in a garden. It has become the catch-all description that draws attention to its staging, and as a result it’s almost totally meaningless.

But did installation art ever denote anything? In the 1960s, the word installation was employed by magazines such as

Artforum,

Arts Magazine and

Studio International to describe the way in which an exhibition was arranged, and the photographic documentation of this arrangement was called an installation shot. The neutrality of the term was an important part of its appeal, particularly for artists associated with Minimalism who rejected the messy expressionistic “environments” of their immediate precursors (such as Allan Kaprow and Claes Oldenburg). Minimalism drew attention to the space in which the work was shown, and gave rise to a direct engagement with this space as a work in itself, often at the expense of any objects. Since then, the distinction between installation art and an installation of works of art has become blurred. Both point to a desire to heighten the viewer’s awareness of how objects are positioned (installed) in a space, and of our response to that arrangement. But there are important differences. A room of paintings by Glenn Brown is not the same as a room of paintings by Ilya Kabakov – because the environment in which Kabakov’s are installed (a fictional Soviet museum) is also part of the work. In a piece of installation art – such as Kabakov’s – the whole situation in its totality claims to be the work of art. Glenn Brown’s paintings, by contrast, exist as separate entities. This totalising approach has often led viewers and critics to think about installation art as an immersive experience. By making a work large enough for us to enter, installation artists are inescapably concerned with the viewer’s presence, or as Kabakov puts it: “The main actor in the total installation, the main centre toward which everything is addressed, for which everything is intended, is the viewer.” He reiterates one of the dominant themes of installation art since it emerged in the 1960s: the desire to provide an intense experience for the viewer. Over the following decade, this activation of the spectator became seen as an alternative to the pacifying effects of mass-media television, mainstream film and magazines. For artists such as Vito Acconci, interactivity could function as an artistic parallel for political activism. As Acconci noted, this kind of engagement “could lead to a revolution”. In Brazil, which suffered a brutal military dictatorship during the 1960s and 1970s, the installations of

Hélio Oiticica (1937–1980), for example, focused on the idea of individual freedom from oppressive governmental forces. He developed the term “supra-sensorial”, which he hoped could “release the individual from his oppressive conditioning” by the state. Inviting viewers to walk barefoot on sand and straw, or to listen to Jimi Hendrix records while relaxing in a hammock, Oiticica advocated the radical potential of hanging out, rather than complying with society’s demands.

Bruce Nauman’s installations of the same period are emphatically less mellow experiences. Although concerned, like Oiticica, with our bodily response to space, his works often thwart our anticipated experience of it through video feedback, mirrors and harsh coloured lighting. His austere video corridors of the 1970s aimed to make us feel out of sync with our surroundings: “My intention would be to set up [the work], so that it is hard to resolve, so that you’re always on the edge of one kind of way of relating to the space or another, and you’re never quite allowed to do either.”

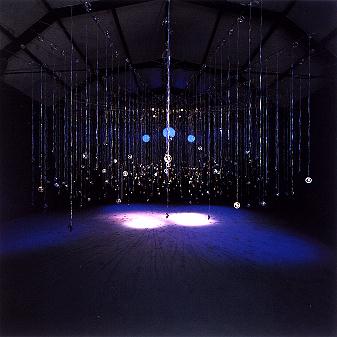

Olafur Eliasson

The Mediated Notion

© Olafur Eliasson. Photo: KUB/Markus Treffer

Installed at Kunsthaus Bregenz 2001

Installation art of the 1980s, by contrast, was more visual and lavish, often characterised by giganticism and excessive use of materials. Think of the inflated gestures of Claes Oldenburg, such as his

Pickaxe (1982), but also the work of Ann Hamilton and Cildo Meireles who continued to prioritise an often disconcerting experience of bodily immediacy. In Meireles’s

Volatile (1980–1994), viewers enter a room of grey ash with a candle at the far end, while the air is permeated with the smell of gas. Describing this work, critic Paulo Herkenhoff wrote that “when you come into contact with danger, your senses become more alert: you not only see but feel with greater intensity”.

The way in which installation art insists upon the viewer’s presence in a space has necessarily led to a number of problems about how it is remembered. You have to make big imaginative leaps if you haven’t actually experienced the work first hand. Like a joke that fails to be funny when repeated, you had to be there. Despite this subjective insistence, most writers agree on the genre’s history: the importance of Modernist precursors such as

El Lissitzky’s Proun Room (1923),

Kurt Schwitters’s Merzbau (1933), Kaprow’s environments and happenings of the early 1960s, as well as the debates around Minimalism and post-Minimalist installation art of the 1970s. They also note its international rise in the 1980s, and its glorifcation as the institutionally approved artform

par excellence of the 1990s, best seen in the spectacular pieces that fill museums such as the Guggenheim in New York and the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern. Some critics, notably those associated with

October magazine, have argued that this trajectory signals the final capitulation of installation art to the culture industry. Once a marginal practice that subverted the market by being difficult – if not impossible – to sell, it is now the epicentre of institutional activity.

Olafur Eliasson

The Weather Project 2003

© Olafur Eliasson. Photo: Tate Photography

But is this really so? Despite the prominence of the Turbine Hall and Duveen Gallery installations at Tate Modern and Tate Britain, only a tiny fraction of installation art is ever acquired for the Collection. With their portability and durability, painting, sculpture, photography and even video are all preferred as safer investments. The Turner Prize has several times been won by video installation artists, but site-specific work has yet to scoop the award, with the exception of Martin Creed’s The lights

going on and off (2001). Instead, it has become the preferred way to create high-impact gestures within ever larger exhibition spaces. It is particularly photogenic in signature architectural statements (think of Olafur Eliasson’s

The Weather Project for the Turbine Hall, or the elaborate installation in Kunsthaus Bregenz, Peter Zumthor’s architectural landmark) or romantically half derelict ex-industrial buildings. And, incrementally, the art form gets closer to spectacle, going all out for the big “wow” instead of meaningful content;

Anish Kapoor’s Marsyas – the vast scarlet trumpet he installed for the arsyas Turbine Hall (2002–2003) – is a good example. Matthew Barney is a similar case: the elaborate re-creations of key sets from his

Cremaster films were toured around Europe before culminating in their extravagant occupation of the entire spiral of the Solomon R Guggenheim in New York. While Barney’s pieces looked great in photographs – and even better in his films – the experience of actually wandering through these grandiloquent sets was depressingly empty.

Anish Kapoor's 'Marsyas' being installed in the Turbine Hall

Photo: Marcus Leith and Andrew Dunkley, Tate Photography

In a recent issue of

Artforum, James Meyer lamented the new trend for museums to endorse “an art of size”. He quoted critic Hal Foster on the Bilbao Guggenheim: “To make a big splash in the global pond of spectacle culture today, you have to have a big rock to drop.” Big audiences are assumed to demand, and like, big works: wall-size video/film projections, oversize photographs and overwhelming sculptures. Rather than “inducing awareness and provoking thought”, wrote Meyer, this type of art is “marshalled to overwhelm and pacify”. Installation art increasingly solicits sponsorship, contributing to a widespread sense among artists and critics that it has reached its sell-by date. Liam Gillick observes that “the word/phrase [installation art] has come to signify middlebrow, low-talent earnestness of production and effect with neo-profound content. This has been compounded by the frequent use of the word to indicate any repressed spectacle in a gallery context”. Gillick, like many, is resistant to labelling himself an installation artist. Thomas Hirschhorn has repeatedly rejected installation as a description of his work, instead preferring the commercial and pragmatic resonance of the word display. Others, such as Paul McCarthy with his

Piccadilly Circus (2003) or

Dominique Gonzales-Foerster, insist that it is just one of many methods they embrace.

While the works of these artists make the visitor feel aware of the space they are in, many in the 1990s placed more emphasis on the viewer’s active participation to generate the meaning of the work – a trend that cultural critic Nicolas Bourriaud described as “relational aesthetics”. For 1997’s

Untitled (tomorrow is another day) Rirkrit Tiravanija re-created his New York apartment at the Cologne Kunstverein and kept it open 24 hours a day, allowing visitors to come in and make food, sleep, watch TV, or have a bath. While Christine Hill made

Volksboutique, a fully functioning second-hand clothes shop, for Documenta X in 1997. In both examples, the emphasis is less on the visual appearance of the space than on the uses made of it by visitors. More experimentally, Carsten Höller has created environments and contraptions, such as his

Pealove Room (1993), a small space in which to make love without touching the ground (it comprises two sex harnesses, a mattress and a phial and syringe containing PEA, the chemical produced by the body when in love), or the

Flying Machine (1996), in which viewers are strapped into a harness and fly in circles above a room, able to control the speed but not the direction of their journey.

Other artists have turned installation art into a branch of interior design. Jorge Pardo’s funky décor for the café bar of K21 in Düsseldorf exemplifies this trend, as does Michael Lin’s pink oriental floor design for the lounge of the Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Pardo has also designed and built a house at

4166 Sea View Lane, Los Angeles, as both, as both his home and a work of art. It was initially subsidised by the LA Museum of Contemporary Art in conjunction with his solo exhibition there in 1998, when it was open to the public. Now it is Pardo’s property, although the museum keeps a public file, and directions to the house, at its information desk. His recent exhibition in London featured photographs of a house in Mexico which he is renovating for sale as a work of art. But unlike installation art that adopts the house as a format – such as Gregor Schneider’s endlessly reworked

Dead House Ur (1984 onwards) – Pardo’s interiors are a backdrop to activity rather than the main event; any interest in perceptual immediacy or the viewer’s consciousness has dissipated into a tasteful design aesthetic, more lifestyle experience than cultural content.

John Block Drawing at the ICA, London as part of Klutterkammer, 2004

Photo: Rose Hempton

Another increasingly visible aspect of installation art is the artist-curated exhibition. Mike Kelley’s

The Uncanny (1993), recently re-staged at Tate Liverpool, is typical in that it operated on two levels: as an exhibition of objects by other people, and as a single work by the artist. For most viewers,

The Uncanny was experienced as a collection of unsettling sculptures and polychromatic human doubles. As the critic Alex Farquharson wrote in a review of the show: “Instead of feeling we were in a modern art gallery, it seemed we’d stumbled on a horror film set, an eighteenth-century anatomy lesson, a hideous crime scene and an occultist tableau.” For those familiar with Kelley’s work, it could be seen as an extension of his interest in psychoanalysis and abjection, and as an exploration of these ideas in an exhibition-installation format.

Klütterkammer, John Bock’s recent show at the ICA, London, complicated this idea further. The network of tunnels, cabins and platforms that Bock constructed around the galleries served to house a selection of strange historical ephemera (such as Rasputin’s fingernails), his own work and that of the people who have influenced him (more than 40 artists, including Martin Kippenberger, Cindy Sherman, John McCracken, Matthew Barney and the Viennese Actionists). Viewers had to crawl along wooden boxes, struggle past woolly obstacles and climb rickety ladders to see the work. All the objects became tainted by the eccentric gloss of Bock’s world view, but made total sense within his haphazard wonderland of tin foil, hay bales and revoltingly felted blankets.

The variety of work detailed above demonstrates that installation art means many things. But, as Gillick observes, to speak of its “end” is extremely difficult, as the term describes “a mode and type of production rather than a movement or strong ideological framework”. Despite the dearth of a manifesto, one can nevertheless point to a persistence of certain ideas in the work of contemporary artists who continue its tradition. These values concern a desire to activate the viewer – as opposed to the passivity of mass-media consumption – and to induce a critical vigilance towards the environments in which we find ourselves. When the experience of going into a museum increasingly rivals that of walking into restaurants, shops, or clubs, works of art may no longer need to take the form of immersive, interactive experiences. Rather, the best installation art is marked by a sense of antagonism towards its environment, a friction with its context that resists organisational pressure and instead exerts its own terms of engagement.

The notion of the installation can be traced back to the second half of the 19th century and in particular to Richard Wagner’s concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk as a synthesis of sensory impressions overwhelming the spectator. Whistler’s decorative scheme of the same period, Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room (1876–7; Washington, DC, Freer), originally designed for the dining-room of his patron F. R. Leyland, sought a similar immersion of the spectator in an experience of beauty encompassing the whole of his or her field of vision; as such it went beyond the impulse to decorate, narrate or instruct, characteristic of church or palace architecture during the medieval period or in the Renaissance.

The most direct predecessors of the installation in its narrower sense, however, are to be found in the international Surrealist exhibitions held during and after the 1930s, notably in London (1936) and at the Galerie Beaux-Arts in Paris (1938); on the latter occasion, music and smells pervaded an entirely enclosed space that included coal sacks on the ceiling, assemblages, plants and paintings.

One of the earliest installations, in the historically precise sense of the term, was Yves Klein’s The Void (Paris, Gal. Iris Clert, 1958), a presentation of the empty white interior of a commercial gallery; a year later another sculptor associated with Nouveau Réalisme, Arman, created Fullness in the same gallery interior by filling the space with rubbish so that it could be viewed only through the outside window. In New York some of the first installations, such as Claes Oldenburg’s The Street and Jim Dine’s The House (both exh. New York, Judson, 1960), each assembled from discarded items found in the streets of the city, were closely linked to performance-art events known as Happenings, which also sought to expand the realm of art by drawing the audience into the physical environment as a total entity. One of the most influential of the artists involved with both Happenings and installations was Allan Kaprow; for his installation Words (New York, Smolin Gal., 1961) he combined numerous sheets and rolls of paper containing random arrangements of words with music played by several record-players, allowing spectators to walk right through this chaotic jumble. Joseph Beuys’s arcane installations, such as Room Sculpture, a collection of his earlier works gathered together for the specific gallery space at Documenta IV (Kassel, 1968), emerged from a similar background of actions and Happenings.

In contrast to these temporary or changeable displays, installations that were more fixed in form were made by other artists as early as the 1960s. In works such as The Beanery (1965; Amsterdam, Stedel. Mus.), for example, Edward Kienholz created detailed environments of real places through which the spectator could walk. Modelled on an actual bar in Los Angeles and built to half-scale, it reproduced its architectural source together with assembled figures, most of them heads in the form of clocks and tape-recorded sounds. As permanent, self-contained structures, such installations do not relate closely to the surrounding gallery space but could in principle be housed anywhere. She, a temporary work created by Niki de Saint- Phalle, Jean Tinguely and Per Olof Ultvedt for an exhibition held in 1966 at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, was similarly enclosed. It consisted of a huge reclining female figure, which could be entered between the legs, with a variety of rooms with machines and further installations inside.

Mark Wallinger

Mark Wallinger